Mind your marketing: why brands shouldn’t ignore neurodivergent consumers

Since marketing’s underlying aim is to influence human behaviour, it’s no surprise we’ve relied on psychology – the study of it – to tell us how to be better marketers.

Social proof and herd mentality are two psychological terms marketers reference a lot. Whether they’re copying someone else (social proof), or influenced by the majority (herd mentality), studies tell us that in a nutshell, most people buy whatever other people think is good.

But what if you’re not most people?

In the past few years, it’s become evident that the neurodivergent population – roughly one in seven people – is consistently excluded from marketing’s one-size-fits-all approach.

But neurodivergent people aren’t a homogenous group. Neurodiversity covers a number of conditions, like autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, dyslexia, sensory processing disorders, and Tourette’s syndrome. People with these conditions are considered neurodivergent because their brains function differently in one or more ways than is considered typical.

On the upcoming episode of the SocialMinds podcast, author and Ogilvy advertising legend Rory Sutherland tells us what accessible advertising looks like for brands and marketers.

Outside the herd

According to David Ogilvy, effective advertising appeals to two buyers: the rational buyer and the emotional buyer.

Emotional buyers make decisions on feelings, desires, and impulses. Rational buyers make purchases based on logic, facts, and analysis.

Google ‘classic car ads’ and you’ll see what he means. It’s easy to spot the signs of both emotional and rational advertising: imagery and a tagline that speaks to adventure and freedom; and body copy sprinkled with facts about the car’s fuel efficiency, safety features or reliability to make buyers rationalise their purchase.

Most neurotypicals aren’t entirely rational or emotional – instead they’re somewhere in the middle. But Rory says the emotional sale typically has less hold on the neurodivergent consumer. Contrary to what social proof and herd mentality tell us about human behaviour, neurodivergent people tend to be rational buyers who are less influenced by what’s popular.

What does this mean? It means brands assume advertising impacts all consumers equally. In reality, this was never the case.

Brands assume advertising impacts all consumers equally. In reality, this was never the case.

Accessibility is a necessary part of the industry conversation, but often it only goes so far. Beyond accessibility in a physical sense – i.e the workplace – brands and platforms must do the work to make sure virtual spaces aren’t left behind.

Trains, planes and TikTok

Old-school advertising hasn’t been the most accessible, or the most efficient, way marketers can make their ad dollars count. In an April 2022 Spectator article, Rory explains that “most television is produced for neurotypical people” – so by nature, TV advertising skews toward this audience. In excluding an entire group of consumers, brands are only getting half the picture.

But the normalisation of video on social has radically changed the way we access content. YouTube’s vast catalogue means neurodivergent individuals with special interests can freely watch on-demand content about these (often niche) subjects.

“YouTube is a notch away from being Wikipedia with video….the vast majority of contemporary content on YouTube now is basically broadcast quality.”

Social has helped usher in a mainstream era for hobbies once considered specialised; even obscure. Remember Big Jet TV? The YouTube channel went viral for live streaming planes landing at London’s Heathrow Airport during Storm Eunice in 2022, revealing a global community of planespotters to the masses.

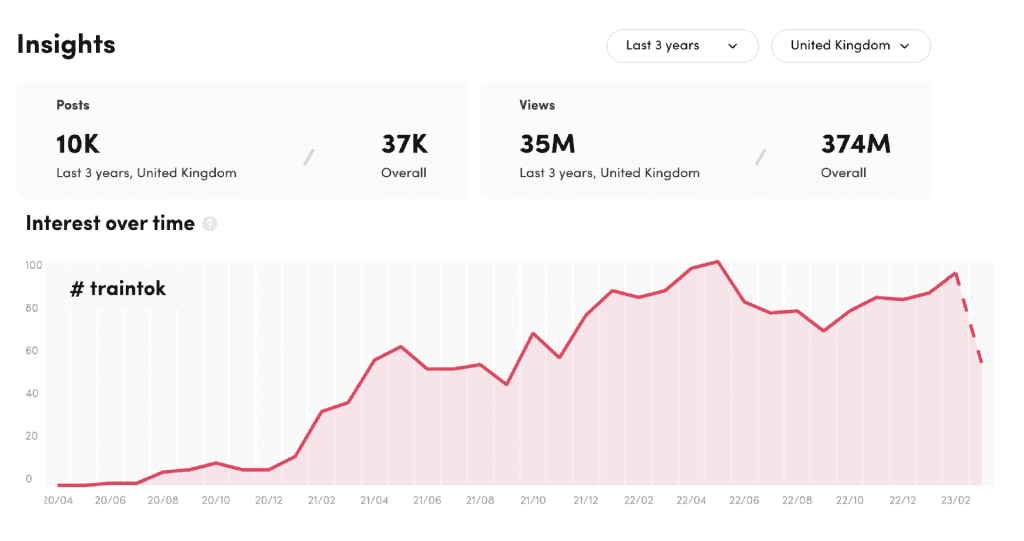

Same goes for TikTok’s resident trainspotter-in-chief Francis Bourgeois. Videos with the hashtag #traintok surged after Francis went viral in October 2021, hitting peak popularity seven months later. He’s also trainspotting’s coolest ambassador – his 4 million-plus online following has secured him deals with Gucci, The North Face and Spotify.

That’s just one example where TikTok is concerned. There’s quite literally a Tok for everything, from books to shoes to butter, each with its own unique potential for brands to discover.

Social platforms are catering to neurodivergent consumers in other ways. LinkedIn, for example, added dyslexic thinking to its list of member profile skills in March 2022.

But they’re also taking steps back. Despite being considered one of the most accessible social platforms, Twitter laid off most of its accessibility team in October last year, prompting concern among Twitter’s accessibility community.

It reminds us that, despite the positives, there’s still a long way to go.

Small topics, big opportunities

An accessible workplace benefits everyone. A flexitime policy lets some neurotypical workers structure their time according to their most productive hours. But it also means those with children can flex working hours around childcare.

The same applies to your content and advertising. If neurodivergent consumers can understand your content and ads, everyone can. Instead of an afterthought, accessibility should be top priority.

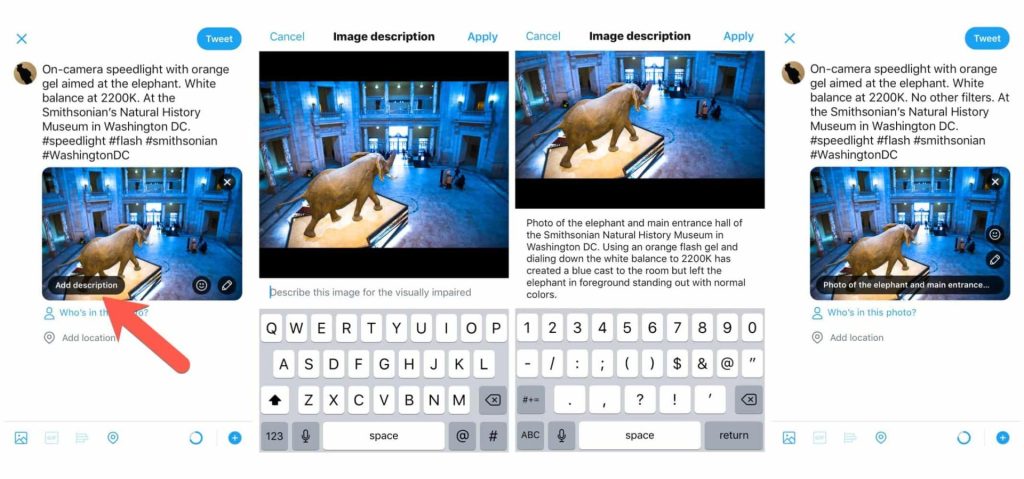

Start with small but impactful changes – like numbering Twitter threads, adding image descriptions, including video captions and using accessible colour palettes for assets, websites and ad creative.

Today’s diversity of content gives brands room to explore big opportunities within small subjects. Sceptics might argue brands can’t thrive at scale if they’re targeting niche topics. But part of what makes TikTok powerful is its ability to house large-scale communities with shared special interests. Maybe you’re not keen on greens, but #saladtok has over 97 million views thanks to viral celebrity salads and green goddess dressing recipes.

Brands need to move past a one-size-fits-all approach, and recognise that the average person doesn’t exist.

“Companies like to treat humans as if they all behave in a predictable, rational way, but we don’t,” says Rory. “There’s no such thing as the average customer. Brands should cater to the outliers for better success.”